Before Calvin Klein was the fashion brand recognized from red carpets and underwear drawers around the world, he was a man from the Bronx with a relentless passion for classic, minimalist Americana. On the occasion of Klein’s new eponymous monograph, Derek Blasberg sits down with the fashion designer to discuss his artistic influences, creative process, and lasting legacy.

Let’s start at the beginning. I know you’ve been approached about writing a book for years and you’ve always been reticent about doing one. Why this book now?

I’ve done a fair amount of speaking to students at universities and what I’ve found is that the name “Calvin Klein” is now known around the world but oftentimes, when I’m talking to twenty-year-olds, they don’t always know the whole story. Some of them didn’t know when I owned the company, and that I was creating all the imagery when I did. I felt it was time to do something that students can have as a reference. Also, [my ex-wife and former studio director] Kelly [Klein] kept saying to me that if I don’t do [the book] someone else will, and I won’t be happy how they do it.

That’s a very compelling argument.

She was right, by the way! She also helped me a great deal on the book. It was fun to work together again. It was interesting and exciting to go through more than 40,000 images, which is what we have in the archive, and narrow it down to what you see here.

I’ve spoken to artists and photographers who’ve worked on books like this and they say it’s almost therapeutic. Did you find that to be the case?

It was exciting, emotional, gratifying, all things that were positive. I used to personally edit all of the prints you’d see in the national advertising campaigns, so when I was looking at them again I was curious if I would still do the same edit today, would I run the same images. Now, I can say, yes, I would. They still feel contemporary to me. I wasn’t sure about that before I started this process but I was pleasantly surprised after I got into it.

How long did the process take?

Three years.

I’d venture to say your career has been about looking forward, not backward, and about being contemporary, not nostalgic. Was looking back an interesting exercise?

That was one of the reasons I’d resisted doing a book, my tendency is to stay in the moment. But especially when I’d talk to these students, I’d realize they needed a point of reference to see how we built a global brand before the Internet. The only way to put that into context was if I edited and put together this volume.

Let’s talk about some of the artists you collaborated with.

The first photographer I worked with was Arthur Elgort, and I learned so much from him. When I got the cover of Newsweek, Arthur took the picture. Looking back at his work and his team, from the very beginning, that vision I had about what was modern and sensual permeated throughout four decades of work. [Richard] Avedon came along later, with the national advertising on television and in commercials and print.

The images in the book are not grouped by era or photographer.

I liked the idea of mixing and juxtaposing images from the ’70s and ’80s against other decades, so that one could see that the vision was the same regardless of the photographer I worked with, regardless of the model or creative director. There was consistency throughout the work. I tell students it’s important to establish an image in your mind of what you stand for. You have to establish a look that separates you from the rest of the crowd.

What was it like to meet Georgia O’Keeffe, and why was she such an important influence to you?

I was always in love with her work. I loved the sensuality of her paintings, the colors, the form, the shapes, everything down to the brushstroke. I had the opportunity to meet her through Robert Miller, who represented her at the time, and I became good friends with Ron Hamilton, who was living with her and taking care of her and was an artist himself. She was extraordinary. I spent time in Santa Fe, which was reflected in the work that I was creating, like the jeans line. All kinds of projects came from there. We photographed at Santa Fe’s Ghost Ranch. She was kind enough to let us invade her life, and she had such a great spirit and sense of humor. That was a very special relationship.

Contemporary art was often an influence in your work.

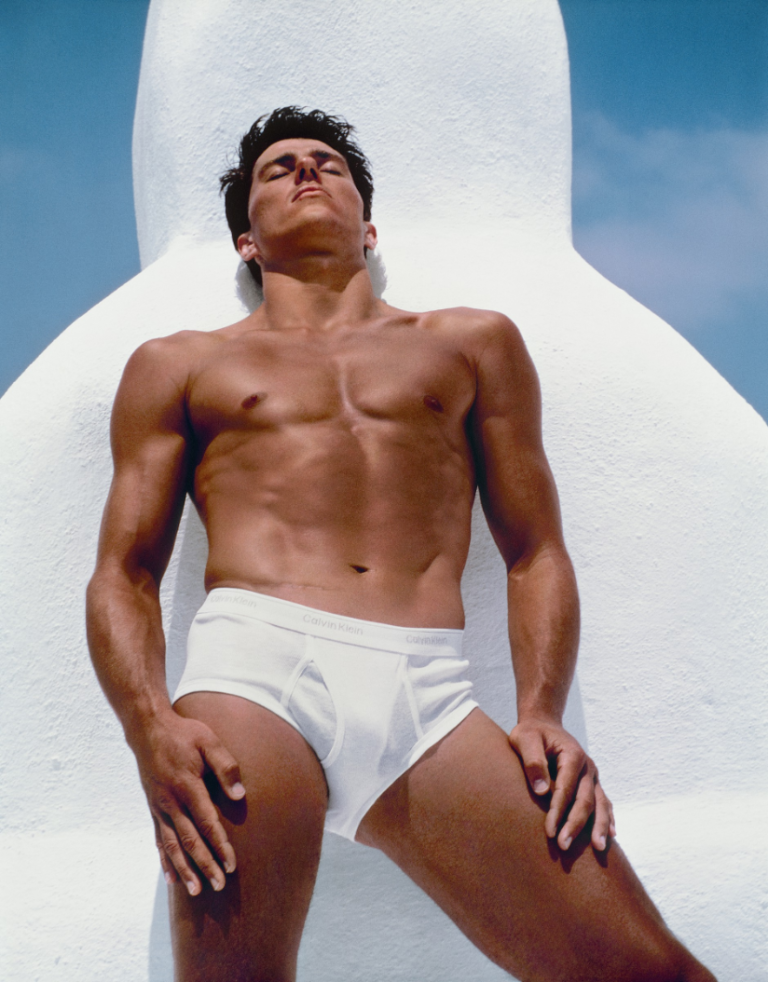

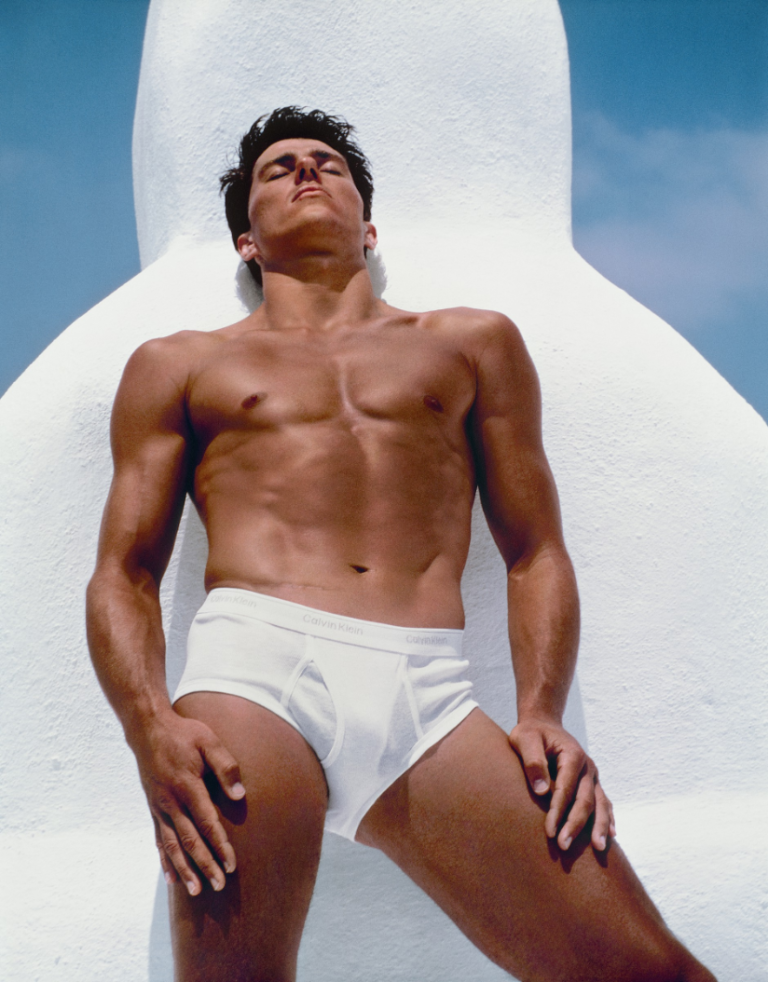

A designer often gets influenced by the world around him or her. While I didn’t know Mark Rothko, he was always a strong influence in my work. His use of color and combinations always struck me as completely inspirational. I didn’t know Donald Judd, either, but I spent time at his place in Marfa, Texas, and made a deep connection to the Judd Foundation. There’s always been a connection and pure inspiration from what’s happening around a designer. It could be architecture, fine arts, nature—it’s all there. Like the picture of Tom [Hintnaus, the model in Klein’s iconic first men’s underwear ad, photographed by Bruce Weber in front of a traditional white chimney in the Greek islands]: had that been shot in a studio and against a seamless it wouldn’t have the impact that it did. It was because we went to Santorini. The sky, the architectural forms—that’s what led to that photograph.

"For me it was organic and natural. I did not seek inspiration."

"For me it was organic and natural. I did not seek inspiration."

The relationship between art and fashion goes back a long way. How have you seen it change?

I think there’s danger when designers become too intellectual and think of their work as art, as opposed to creating clothes—when they take themselves too seriously. I’ve seen this in recent years: designers can be influenced by art, of course, but they are creating clothes, things that people wear and that become a part of their lives, things we interact with differently than we do with art. We have the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the clothes that are in there belong in a museum because it’s the idea of being retrospective.

What’s the secret to distilling what’s around us into a singular vision?

I learned early on to trust my instincts. I would get an emotional reaction when I saw things—sometimes my heart would race and I’d know I was on the right track. For me it was organic and natural. I did not seek inspiration.

Talk to me about the models you worked with. How did you find the faces of Calvin Klein?

I love discovering new faces. From early on, I’d have castings and scout the world. I’d get Polaroids of people from friends when they saw someone they thought I’d be interested in. Sometimes I used talent with model agents but most of the time not. I always had a strong feeling about how I would communicate to the man or woman who was buying my designs, and I’d have a strong feeling about who could embody that feeling. It was as important to me as choosing the photographer, the location, the hair and makeup artists. It was instinctive.

I found Tom when I was in LA, driving down Sunset Boulevard. I saw him running, stopped the car, got out and introduced myself, and almost instantly asked him, “Have you ever been to Greece? Want to go next week?” That’s an example of how I could spot the person and know instantly if they were right. Other times I had to go through hundreds of Polaroids that were sent to me. An example of that would be a young man from Australia who I put in an underwear campaign. He was a surfer and I looked at a Polaroid and said, “I’d like to meet this one.” We got him to my studio within days, and he became the last male underwear model that I personally put on contract.

I remember that campaign: his name was Travis Fimmel, and there were reports that his ads were causing accidents because drivers were distracted. He stopped traffic, literally.

Yes, that’s true! Early on, when we ran Tom, the posters were on bus stops and the parks department called to say that people were stealing them. They were under glass! I asked, “How much does that cost?” The guy says, “It costs $500 to replace the glass,” so I said, “Let them steal them and I’ll pay for it.”

When you’re marketing and when you’re shooting the pictures, you don’t know what the result will be, but we could always tell what was exciting because it would get us excited. We always tried to do something that was creative and pushed the envelope too. I was always thinking, when I was advertising in a magazine like Vogue, what would make people stop at my spread? Sometimes I’d advertise six pages, sometimes thirty-six—I just wanted to capture people’s attention. I never thought I’d cause traffic accidents or bust up bus stops, but I wasn’t unhappy when that happened either.

Tell me about Kate Moss.

I didn’t know she’d become a sensation when I met her. I’d just been to Paris and I was looking at what the other designers were doing. I went to some shows and saw women I’d used before, and I thought, “That’s not terribly exciting to use the same faces and bodies everyone else uses.” I came back from that trip and wanted a different type of woman for what I was trying to say. I was thinking of this young actress at the time, Vanessa Paradis, but she was busy doing a film. I discussed all this with Patrick Demarchelier, and Kate ended up in his studio and he called me to say, “I think I have what you’re looking for.” I met Kate and looked at these pictures that her boyfriend at the time, Mario Sorrenti, had taken of her, and it just said “Obsession” to me. I was looking for a new face to bring the fragrance into the ’90s and this was it. I found lots of young women who were like Kate too: a new type of body, a new androgyny that was also sensual and sexy, a new everything. The press would call it “the waif.” Fashion is about change and evolving, and you have to find new ways to excite people.

When I read the book, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of family. It’s dedicated to your daughter, your former wife helped put it together, there are so many of the same models, photographers, and creative directors. Is this not the chic-est fashion-family photo album?

I love the way you put that! I always thought of it like “This is my life. This is my life’s story.” Yes, it was family. My relationships with Bruce, Arthur, Dick Avedon, Sam Shahid, Fabien Baron: they helped make what I had in my mind come to life. The women, the men, Christy [Turlington] and Kate, Beverly Johnson, Janice Dickinson—it was gratifying and exciting and emotional for me to work on this book.

Was anything particularly hard about doing the book? Or easy?

It was work, from beginning to end. It required dedication and focus. This all comes from my passion for creativity, for design, for fashion, as well as beauty, makeup, and all kinds of things that I was involved with. It’s about loving what you do. I was bringing it all together in a single statement about what we were able to accomplish over those years to build a global brand, which was exciting and ultimately my life’s work. It wasn’t easy, but it was wonderful.